Discover more from Ettingermentum Newsletter

The Modern Electoral History of Transphobia

How trans hatred has been a consistent liability for Republicans, and why the right refuses to give it up

Of the massive trail of destruction wreaked by American movement conservatives, their persecution of sexual and gender minorities has been one of their most utterly vile projects. Out of murderous bigotry and a desire for votes, they have spent decades leveraging the power of the American state to make the lives of LGBT people as miserable and short as possible. From the genocidal neglect of the HIV/AIDS crisis, to the criminalization of the most basic acts of daily life, to the constant demonization of innocents to win votes, the right has committed innumerable atrocities to destroy the lives of LGBT people. Throughout it all, their only limits have stood where their hatred started becoming a political liability.

And one of the most spectacular stories in modern American history has been how these limits have changed. Over the past few decades, public opinion on LGBT issues, represented in the debate over same-sex marriage, has shifted to an extent and at a rate with few parallels in political history. Starting around the mid-2000s, support for same-sex marriage changed from a solidly outnumbered minority position to a stance with supermajority support among the public—over the course of a single decade. It happened with such speed that it caught nearly every person in power off guard. Politicians who had previously opposed same-sex marriage, from Barack Obama to Hillary Clinton, began tripping over themselves to move to the left on the issue. Reactionaries woke up to find a once-potent wedge issue now acting as an anchor with ever-increasing weight.

In 2015, these seismic shifts in public opinion culminated in the Obergefell v. Hodges ruling, which legalized same-sex marriage nationwide. After this, it seemed for a time that there might—mercifully—be something of a thaw in the politics of sexual and gender identity. During the 2016 election, the issue more or less receded into the background, especially following the nomination of Donald Trump. While the 2016 Republican platform still called for the primacy of “traditional marriage,” the 2016 Republican nominee would refrain from establishing a clear stance on the issue one way or the other. At one moment, he would even cast himself as a better “friend” to the community than Hillary Clinton or Barack Obama—albeit with the aim of further demonizing Muslims after the Pulse nightclub massacre in Orlando, Florida.

Of course, none of it was sincere. As easily as Trump would make this sort of outreach, he would also promise to overturn Obergefell and put out lists of potential Supreme Court nominees who were very likely to do so. For his running mate, he would pick a leader of the Christian right, notorious for his homophobia even within the Republican Party itself. Still, even mere changes in rhetoric were still remarkable to see compared to how the party had previously dealt with the issue. And while Trump’s ultimate victory could never be construed as anything near a progressive development, the way in which he won—winning over support from traditionally Democratic voters who saw him as an independent moderate—perhaps could have represented proof to Republicans that they might be best served leaving issues of sexuality and gender be.

A little over six years since then, we now know this would not happen. Right-wing attacks on sexual and gender minorities did not end with their retreat on issues like gay marriage. Instead, they simply found a new target: transgender people. Starting with so-called “bathroom bills” in the mid-2010s, continuing with the shifting and escalation of attacks during the Trump administration, and expanding rapidly at the state level throughout the Biden administration, the assault on transgender rights has grown to be one of the most important issues in American politics today. Discrimination against transgender people is now one of the main parts of any modern red-state policy agenda. Demonizing transgender people is now central to nearly every Republican political campaign. And the ultimate aim of their scheme is clear: the criminalization and eradication of non-traditional gender identities.

The aim of this piece is to account for the political nature and history of this scheme.

To be clear: I do not aim to or purport to provide a cohesive accounting of transgender history or the transgender experience in America. As a straight, cis man, under no circumstances would I be able to do so. What I am attempting to provide is something of a working electoral history of transphobia: the story of its ascension to the core of Republican campaigning and governance over the past decade and how it has performed in elections. My ultimate hope is to prove a simple fact beyond any reasonable doubt: that trans people and trans rights are not liabilities to any left-wing movement in any sense of the term, and that anybody who has ever spoken of them as such is either a disingenuous transphobe or too stupid and lazy to ever be taken seriously.

With that in mind, let us turn to the place where our story begins: North Carolina, U.S.A.

2010-2016

As is the case for much more in modern American politics than is realized, the genesis for the first major political confrontation over trans rights was the 2010 election. By the close of the aughts, the Democratic Party of North Carolina was riding high. They held both houses of the state legislature, just as they had done almost continuously since the 1890s, and with their new governor, Bev Perdue, they held a trifecta. Perdue was the state’s third consecutive Democratic Governor, and her victory in 2008 marked 20 years since the last time a Republican had won the office. The state had even just voted Democratic for President, the first time it had done so since 1976! Even within a party that had just had one of the most successful two-year runs in political history, they were a remarkable success story.

But in the 2010 midterms, everything would go south, marking a dramatic, long-term political shift in the Tar Heel State. Amid an utter brutalization of Democrats across the country, North Carolina Democrats faced catastrophic losses, losing control over both houses of the state legislature to Republicans for the first time since Reconstruction. While Perdue remaining Governor meant that they would not hold a trifecta, the peculiarities of state law meant that Republicans would have unilateral control over the only thing they truly needed to have authority over: redistricting. While the North Carolina Governor is far from a figurehead, they play no role in how the state’s districts are drawn after each census, giving the newly Republican state legislature a free hand to draw whatever maps they wanted. These maps would be brutal gerrymanders, structured to provide the party with perpetual supermajorities.

These maps would work like a charm in the 2012 elections, expanding the party’s ranks in the General Assembly by nearly a dozen members despite an electorate that was far less Republican than the one that voted in 2010. Even more importantly, the party would resoundingly win that year’s gubernatorial election. Governor Bev Perdue had become so unpopular during her tenure that she would not even run for a second term, and the nominee in her stead, Lieutenant Governor Walter Dayton, would be crushed by Pat McCrory, the Republican nominee and former mayor of Charlotte. While Barack Obama would lose to Mitt Romney by only two points in the concurrent Presidential contest, Dayton fell by 12, losing 55 to 43.

Even at the time, commentators could tell that this Republican ascension was going to be far different than the usual coming and going of party power. Seemingly overnight, a political class that had long been known for a moderate, pro-business approach was replaced wholesale by a group of ideologically motivated movement conservatives—set up by their own maps to hold power indefinitely. And they had lofty aims. North Carolina, along with other states with historically moderate politics like Wisconsin and Kansas, was selected by national movement conservatives as a “laboratory:” where the new right-wing governments would enact as many extreme, far-right policies as possible.

They would hit the ground running. Despite McCrory having run a moderate campaign—he even disavowed increased restrictions on abortion!—he and the state legislature would launch head-on to the fringe immediately after he assumed office. Unemployment benefits were cut massively. Civil rights bills were repealed. Voting was made less accessible and more onerous for voters. Access to abortion was restricted, despite promises. The Governor would personally opt out of expanded Medicare programs, barring half a million North Carolinians from receiving health insurance. All of this would lead to regular protests that received national attention, but Republicans, having ensconced themselves in power so thoroughly, paid little mind. The state’s first verdict on their actions in the 2014 elections would come and go as another success for the party. They would flip the state’s only Democratic-held Senate seat from blue to red, win another U.S. House seat, and face minimal losses in the state legislature.

In response, the state’s left-leaning municipalities and local governments would begin marshaling their authority to stand against the agenda being pushed by the state government. One body in particular, the Charlotte City Council, saw attacks on LGBT people as a potential flashpoint. Starting in 2015, they debated passing an ordinance prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation in public accommodations or by city contractors, but the initial bill would fail for lacking provisions regarding gender identity. In early 2016, the bill was revised to include such provisions, and it would be passed on a 7-4 vote as Charlotte Ordinance 7056.

Charlotte did not pass this ordinance randomly. While the legislation that would eventually be referred to as “bathroom bills” had not yet been passed in any state, they had begun to be considered by various state legislators across the country starting around 2013. All so far had died without passing a single state legislature, but they started occurring with increased frequency after the creation of model legislation by the Alliance Defending Freedom (formerly known as the Alliance Defense Fund), a conservative Christian organization and anti-LGBT hate group. Since the North Carolinian state had been firmly co-opted by such national organizations, it made perfect sense to pre-empt potential efforts by McCrory and his allies before they happened. After all, the state had been selected to be on the bleeding edge of far-right policymaking.

But even though their action was a conscious confrontation with the state government, Charlotte legislators would be shocked at the speed and ferocity with which McCrory and his allies responded to their efforts. The Governor would refer to the ordinance, passed by the very city he used to govern, as an outright public danger, and threatened to call in a special session of the legislature specifically aimed at targeting it. On March 22nd, he would do so, and on the 23rd, the first day of the special session, the North Carolina state legislature would pass the Public Facilities Privacy & Security Act, commonly known as House Bill 2, or HB2. This bill, passed along party lines, declared that state law would have primacy over local anti-discrimination laws. As North Carolina state law had no explicit protections against discrimination on the basis of sexual or gender identity, this effectively repealed measures like Charlotte Ordinance 7056. In the place of these ordinances—and local control over the issue—the law mandated that schools and public restrooms across the entire state restrict access to gender-segregated bathrooms to the sex on an individual’s birth certificate. It also outlawed any increases in the minimum wage by municipal governments, just for good measure.

It took only 11 hours and 10 minutes to pass.

Politically, North Carolina Republicans likely expected this to be an issue where public opinion would be in their favor. And at the time, there were some reasons to think so. The prior year, a very similar non-discrimination ordinance was passed in Houston and met swift backlash that culminated in the Texas Supreme Court ordering that it be subject to a ballot measure. In that election, held in November 2015 with low turnout, opponents to the ordinance scored a landslide victory, repealing the measure by a margin of 61-39.

This was in Houston, a major city! If an anti-trans push could receive that much support there, of all places, it must have looked like an excellent opportunity for North Carolina Republicans to press on heading into the 2016 elections. And as much as bathrooms may have looked like a peculiar topic to focus on, there was a surprisingly rich history of movement conservatives leveraging them in their campaigns. Manufactured fears that the Equal Rights Amendment would result in the abolition of gender-segregated bathrooms played a major role in the 1970s campaign to defeat said amendment. After a year of devastating setbacks on the cultural front, conservatives thought, perhaps this throwback was just what they needed to find their footing.

It would end up being absolutely nothing of the sort. The backlash to the bill would be swift and harsh, beyond anything expected by even the most optimistic of the bill’s opponents. Instead of a reasonable protection against overbearing cultural liberals, HB2 was broadly seen as, at best, an overly broad solution in search of a problem. At worst, it was seen as mandating discrimination against the LGBT community, an undeniable act of legal bigotry that made even the mere act of visiting the state a moral dilemma. Not only was it unpopular with voters, it went as far as to ruin the image of the state in the eyes of the nation, particularly—and most importantly—to big business.

What followed next would define how the politics of trans rights would be understood for years to come. Faced with the question of complying with the new law, big businesses, even firms with a long history in the Tar Heel State, began pulling out en masse. The NBA canceled plans to hold the All-Star Game in Charlotte. The NCAA pulled several events from the state, including the national men’s basketball tournament, and declared that the state would not receive consideration for hosting future events until the law was repealed. As hosts for such events are decided years in advance, it was an especially big threat.

Within a month, over 200 CEOs and business leaders would call for the law’s repeal. When it wasn’t, the dominoes started to fall. PayPal canceled a 400-job project in Charlotte. CoStar backed out of negotiations to bring over 700 jobs to the same city. Deutsche Bank sank a 250-job project in Raleigh. Adidas chose to build their first U.S. shoe factory in Atlanta after previously considering High Point. Voxpro, a customer service firm, chose to hire hundreds of workers in Atlanta rather than the Raleigh area, as, in the words of the company’s CEO, “We couldn’t set up operations in a state that was discriminating against LGBT people.”

All told, the cumulative economic costs of the pullouts and canceled events as a result of HB2 has been estimated to have been nearly $4 billion over the course of 2016. And even this number is certainly a low estimate. It only includes the costs of projects that were planned ahead of time and canceled as a result of the law. The true cost of the law, including new projects that may have considered North Carolina but didn’t because of HB2, will never be known.

These boycotts immediately changed the politics of HB2, putting supporters of the law in an unwinnable position. It would have been one thing if the debate had simply been a question of tolerance or intolerance towards the LGBT community. But now, it was a question of accepting massive economic losses in order to discriminate against a minority group most North Carolinians had never met and had nothing against. For most voters, there was no discussion. The vast majority of North Carolinians were confused and outraged that their state had seemingly become a national pariah overnight in the service of one side of a cultural debate they had never even thought about before.

The bill quickly became deeply unpopular, both in North Carolina and the country at large. A national survey by CNN in May showed that nearly 60 percent of Americans opposed laws forcing transgender individuals to use facilities that do not match their gender identity. It was a result that was especially remarkable to LGBT advocates, as 85 percent of respondents in the survey said that they had never even met a transgender person before.

One would think that, in the election year for all of North Carolina’s statewide offices and with the fate of an entire ideological project in the balance, Republican leaders would recognize that this would be nothing but a liability for them and adjust accordingly. In a different era, they might have done so. But the new class of movement conservatives who controlled the state refused to recognize that they could have possibly made a mistake, or, at the very least, a mistake that they could not spin their way out of. Encouraged by national conservative groups, they started telling themselves that, despite strong public disapproval of the law, they could still turn it into a winning issue by presenting it as an abstract question on the nature of gender identity. It was an incredibly arrogant stance, willfully ignorant of one of the most basic rules of politics. They insisted upon it anyway, trying to turn a losing proposition into something it wasn’t and never could be.

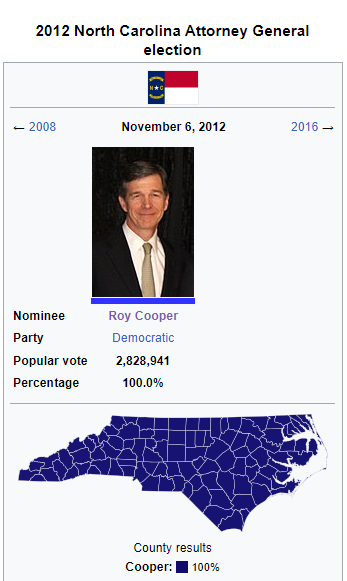

Among all the tumult, one man stood to take singular benefit from the furor surrounding the new law. Enter the man of the hour: Roy Asberry Cooper III, the Attorney General of North Carolina.

In North Carolina politics, Cooper was a unique breed. He was a rural Democrat in a party increasingly dominated by urban professionals, and a popular Democrat in a state that had taken a hard right turn. He was narrowly elected Attorney General in 2000 and had only become more popular since, winning by over 10 in 2004, over 20 in 2008, and going outright uncontested in 2012. In the final case, he would still appear on the ballot, meaning that, in his most recent race at the time of the 2016 election cycle, he had received one hundred percent of the vote and won every county

Even taking increased polarization into account, Cooper likely could have held the office of Attorney General for as long as he wanted to. But it had long been an open secret in North Carolina politics that his ultimate goal was the Governor’s office. Polling between him and Governor McCrory had been conducted since mid-2013, and he would officially announce his candidacy in November 2014. But despite his popularity as Attorney General, the odds didn’t look good for Cooper heading into the election. In the polls throughout 2015 and early 2016, he failed to consistently find a lead against McCrory, at times trailing by five points or more. While it was still early, not even the most optimistic Democrats would have said that the race was anything better than a toss up.

HB2 changed everything. As both McCrory’s primary political opponent and the state’s chief law enforcement officer, Cooper was in a prime position to lead the opposition to the law. He did so with gusto. In his capacity as Attorney General, he announced that he would not enforce the law and refused to defend it against suits in court. In his campaign, he called upon McCrory to repeal the law immediately and blamed the economic effects of it on him personally. It was such an effective counteroffensive that the only response from Republicans was to whine that he was using his office for political purposes. They would be ignored.

All of this would be a massive boon for Cooper’s campaign. Before HB2, the two were neck and neck in the polls. After it, Cooper took a lead over McCrory that he would never relinquish. Just in April alone, one poll had him up by four. Another had him by five. Another had him up by six. A Republican internal even had him up by nine.

As the election came closer, Cooper’s turned fortunes seemed to be less of a unique case and more as just part of the season: right-wing overreach and voter backlash. Donald Trump was named the Republican nominee and was seen as the underdog against Hillary Clinton. North Carolina’s Richard Burr was seen as a strong incumbent by any measure, but even he started falling behind in the polls against his opponent, Deborah Ross. After an up-and-down campaign, forecasters came into Election Day with Clinton as a narrow favorite over Trump in the Tar Heel State. Burr was seen as a favorite, but with a legitimate chance of losing.

None of it would translate. Despite expectations that the state’s presidential contest could take days, if not weeks, to finally call, Trump would win North Carolina decisively, beating Clinton by nearly 200,000 votes, a margin of about four percent. Burr would easily dispatch Ross by six percent. Even in a night that was full of catastrophes, it was a notably crushing result for Democrats. North Carolina was supposed to be the future of the Democratic Party. But after all the issues they tried to pin on Republicans—all the racism, misogyny, xenophobia, even sexual assault admitted on tape—nothing seemed to come through.

That is, except for one issue.

While other Democratic efforts in the state, and the country, were going down in flames, Roy Cooper would hold a lead of around five thousand votes over Pat McCrory by the end of election night. After a campaign dominated by the issue of trans rights, state Republicans were not only unable to benefit from their opposition to it, but ended up driving tens of thousands of Trump voters to split their tickets in favor of a Democrat. In a highly partisan, racially polarized state, during an election where down ballot races were decided at the top of the ticket more than any other in recent memory, it was a stunning result. No other Democrat in a major race in a competitive state put in anything resembling Cooper’s overperformance, much less won their race outright.

McCrory would be one of only three incumbent Republicans in the entire country to lose a statewide election in 2016. Among incumbent Republicans who ran in a state Trump won, he stood alone as the singular loser.

McCrory and the North Carolina Republican Party would contest the results for about a month, but to no avail. Roy Cooper would be inaugurated as North Carolina’s 75th Governor on New Year’s Day, 2017, putting the far-right experiment in the state on hold for at least four years. And it was all because of HB2. After years of moving the state far to the right with no blowback from voters, North Carolina Republicans had finally found their limit—and hit it hard.

2017-2019

Trump’s ascension to power brought new life to even the most forgotten far-right causes. His platform was so broad, and his personal commitment to any program was so lacking, that practically anyone could have spun his victory as a confirmation of their previously existing views. Transphobia was one of the few exceptions. Following the harsh lesson that was Roy Cooper’s victory, even the most deluded Republican could not deny that they had made a mistake on that front. So, they did something that was highly out of character for their new, Trump-dominated party: they retreated.

Of these actions undertaken by Republicans during the early Trump era, the most notable and symbolic would be the partial repeal of HB2 by the North Carolina legislature. The extensive gerrymandering of the state’s maps meant that Cooper would not see any coattails down ballot—in fact, Republicans would actually retain a supermajority in both chambers—but the combined political and economic costs of holding up a clear losing issue proved to be too much for North Carolina Republicans to bear. In late March, almost a full year to the day after the bill’s passage, now-Governor Roy Cooper would sign a compromise bill that repealed the most objectionable parts of HB2 and set in a three-year sunset provision for the rest of the legislation. While hardly comprehensive—even the proudly bipartisan Cooper couldn’t advertise it as anything more than the best deal Republicans were willing to give him—and mostly aimed at satisfying the narrow demands of business groups, it represented a significant retreat on an issue that right-wingers had promised would be a boon for them just one short year prior. And with the sunset date scheduled during Cooper’s term, full repeal of the law was now only a question of when, not if.

As for the rest of the Republican Party, their approach to the issue was mixed. In red states, some legislators attempted to make pushes for their own bathroom bills, but all the bills would eventually fail due to resistance from wary co-partisans. The Trump Administration, for their part, adopted a retrogressive stance towards trans rights. These efforts, however, were fundamentally reactive, rather than proactive, and consisted almost entirely of just the ending of Obama-era policies, rather than the creating new restrictions that did not exist before.

Of these efforts, the one that would receive by far the most attention was the administration’s July 2017 decision to bar transgender individuals from serving in the U.S. military. This, like most of Trump’s policies, was crushingly unpopular. Polls would register between 60 percent and 70 percent of the public as disagreeing with the ban, and while it was by no means the cause of Trump’s chronically low approval ratings, it certainly didn’t help. Following the announcement of the policy, the President’s approval would fall from 39 percent to 37, a mark that would eventually stand as the second lowest of his entire tenure.

On the campaign trail, there were two major statewide elections scheduled in 2017: dual open governorships in New Jersey and Virginia. In both races, beleaguered Republican nominees would look to transgender issues as a place where they could take a popular, moderate stance to separate themselves from a deeply unpopular President. In the Garden State, both Republican candidates for Governor, Kim Guadagno and Jack Ciattarelli, attempted to defuse the issue, with Guadagno going so far as to explicitly pledge support for the community. In Virginia, the Republican nominee for Governor, Ed Gillespie, did the same. Despite mostly embracing Trump throughout the election, he went out of his way to break from the President following the announcement of the transgender military ban (although still making clear that he opposed the military covering trans healthcare). In October, he went even further: in an attempt to win the support of a North Virginia business community, he pledged to oppose any North Carolina-style “bathroom bills.”

Not all Republicans would take such a waffling stance, however. For instance, Bob Marshall, a long-tenured NoVa Republican in the Virginia General Assembly, announced steadfast support for Trump’s policy, making a now-familiar case that transgender healthcare constitutes “costly and risky elective surgeries and decades of synthetic hormones that can cause cancer.” And if his stance on the issue wasn’t clear enough, Marshall would introduce his own bathroom bill to the state legislature. Both Marshall and Gillespie would face criticism from a local journalist and political candidate named Danica Roem, who said that the latter was “full of it” and called the former an “extremely predictable” discriminator and liar.

Voters would agree with her. On election night, Guadagno and Gillespie would go down in defeat. Even with their attempts at moderation on LGBT issues, they ended up losing by 14 and nine points, respectively, to their Democratic opponents. As for Bob Marshall, he would go down in defeat to Roem herself, losing by nine points in a district he had represented for over 25 years. This made Roem the first openly transgender state legislator in U.S. history.

This may create an impression that the stances made by Republicans on trans issues don’t really matter. A closer look, however, shows that their more moderate approach of Guadagno and Gillespie may well have benefitted them. Despite running at what would be the nadir of Trump’s popularity, both gubernatorial candidates did better than Republicans would ultimately do in congressional elections in the following year’s midterm elections. In Virginia, Gillespie would win a district around the Richmond suburbs that would eventually be carried by Democrats in 2018. In New Jersey, Guadagno won two districts in the center of the state that would also later flip blue. If all Republicans in the country were able to perform at the level of Gillespie and Guadagno in 2018, they likely still would have lost the House—the Democratic majority elected that year was just too large. But they very well could have won it in 2020, when Democrats maintained a razor-thin majority in large part because their incumbents in those three districts managed to narrowly hold on.

But if Marshall wished to go down in history as the biggest transphobe to lose an election in 2017, he would be topped by Roy Moore, the Republican nominee for Senate in a special election in Alabama, only a few days later. The same week that his co-partisans went down in defeat in Virginia and New Jersey, Moore bluntly declared on November 8th, 2017 that “the transgenders don’t have rights.”

The following day, on November 9th, the Washington Post alleged that Moore was a pedophile who had made sexual advances on a 14 year old at the age of 32. Following this, his support would collapse. Although he would maintain his endorsement from President Trump, an allegedly less old-fashioned but just as prolific pedophile, he would ultimately go down in humiliating defeat to Doug Jones, the Democratic nominee, in the December election.

It was one of the most catastrophic election losses in modern political history. Virulent anti-trans rhetoric did nothing to stop it. Not even in a state as red as Alabama.

As 2017 passed to 2018, it would mark the end of legislating season and the beginning of campaign season at both the state and federal levels. And as Trump’s approval rating remained mired in the high 30s and low 40s, Republicans found themselves on a death march to November. While there was some posturing to the media that they could defy expectations like 2016, everyone knew that the only real question of the year would be the extent of their losses. As for messaging, the party’s brand would be outsourced entirely to Trump, whose influence over the GOP, now firmly established, was at its zenith. At the same time, Democrats believed that they had found their message, which would focus on issues like healthcare and taxes, where the party had its broadest appeal. Thus, cultural issues, including trans rights, would take a backseat during the campaign, which Democrats preferred and Republicans had no choice but to accept.

Whatever choices either party made likely wouldn’t have mattered much either way. It was a campaign that functioned solely as a referendum on an unpopular President, and, as such, he and his party were rebuked decisively. But unlike most presidents, Trump was uniquely lacking in his capacity for self-examination—his first response to the midterms was to say that he won them—and as he held complete control over the Republican Party, he made sure that no moderation from his line would be allowed within the GOP. Republicans knew that the only movement that would be acceptable was to go ever further to the right.

And for the next slate of elections in 2019, Republicans had a chance to test out exactly such a movement. Every year before a Presidential election, three states hold gubernatorial contests: Kentucky, Louisiana, and Mississippi. All are deeply red states, but in that cycle, two—Kentucky and Louisiana—had specific circumstances that made them meaningfully competitive. In the case of Louisiana, the incumbent Governor, John Bel Edwards, was a Democrat, elected in 2015 against a scandal-ridden opponent but largely seen as vulnerable in his bid for re-election due to the state’s strong Republican lean. In Kentucky, the incumbent Governor, Matt Bevin, was a Republican, but had grown to become deeply unpopular over his tenure and was also seen as potentially beatable despite his state’s far-right lean.

It was a very familiar dynamic for Republicans: a Democrat in a deep-red state, usually in the South, is abnormally popular as a result of their personal appeal or strong incumbency advantage, and the best path to take them out is by leveraging cultural issues. They had run this same race hundreds of times and, by that point, defeated practically every Democrat not named Joe Manchin doing it. Governor Edwards, a blue dog, was a little too conservative to pull this off perfectly. But when Democrats in Kentucky nominated the state’s pro-choice, pro-LGBT Attorney General, Andy Beshear, to challenge Bevin, Republicans thought they had found their perfect target—and perfect subject for experimentation. For this race, they decided to focus on a new issue: the participation of transgender teenagers in school sports, specifically girls’ sports.

This would be the start of the second stage of post-Obergefell political transphobia, and it represented the long-delayed Republican response to the failure of their “bathroom bills”. The logic was simple: they would reduce the scope of their attacks, changing their target from all transgender individuals to just trans kids, and couple it with a massive expansion of messaging on the issue. Almost overnight, the question of transgender teenagers supposedly destroying girl’s sports became central to Republican attacks on Beshear. A far-right D.C. think tank called the American Principles Project—initially founded to advocate for a return to the gold standard—shot commercials, sent out tens of thousands of texts and ran countless online ads accusing Beshear of supporting “putting boys in girl’s sports.”

For a new attack on an issue where they had lost before, there was a remarkable lack of subtlety on the part of the Republicans. Before even bothering to introduce the issue to voters, ads aired claiming that a crisis was at hand, outright saying that teenagers were transitioning with the sole purpose of beating cisgender girls in sports. And just in case this wasn’t dirty enough, they used footage of a cisgender male athlete in their ads to portray a trans girl. This, the APP said, is what Andy Beshear believed in. He was “too extreme for Kentucky.”

It would have been easy for the Beshear campaign to concede on the merits of the issue to try to prevent further attacks. To their credit, they refused to do so. Rather than shirking and saying that they actually opposed what the ads were describing, Beshear accused the APP of not just lying, but trying to bully children. The APP, for their part, refused to budge. Sure, they admitted, the bathroom angle didn’t work out as they hoped. But this, they claimed, was different. They said they even had polling to back it up. While messages about bathrooms supposedly “barely moved” voters to Republicans, messages about girls’ sports were said to move voters towards Bevin by between “four to seven points.”

For transphobes, this was supposed to be their moment: the time they finally proved their worth electorally, provided Trump with a new message for his re-election campaign, and saved a floundering Governor in the process.

It was a complete flop.

Despite trailing in the polls at the time of the election, Andy Beshear would defeat Matt Bevin, flipping the office blue and making Kentucky by far the reddest state with a Democratic governor. For groups like the APP, it was an utter humiliation. North Carolina was one thing, but failing at right-wing culture war messaging in Kentucky? A state that voted for Trump by 30 points? It was a level of inefficacy without parallel. For a project that was supposed to be the future of the culture war itself, they could have not given off a worse first impression.

If this showing was truly supposed to decide if transphobia would have a future in Republican messaging, the entire project would have died then and there. But politics is not always what plays the best electorally. Despite completely failing to convince voters, transphobic messaging was winning over a different audience: conservative activists. Ultimately, early efforts by groups like the APP proved to be less of a one-time experiment and more of the opening of a Pandora's box. Over the next few years, conservatives, both old and new, would become hopelessly obsessed with trans issues and trans people—with disastrous results for their electoral strength.

2020-2022

Over the course of the 2020 election, the first place where trans issues would receive attention would be the Democratic Presidential primaries, where candidates would rush to announce support for the community. Some positions were helpful and called attention to long-ignored issues. Other positions amounted to bizarre, heavy-handed pandering that would have done nothing to address the community’s many material concerns. In other words: politics as usual. After years of being ignored or, in the worst cases, outright mocked by the powers-that-be in left-of-center politics in America, relentless activism, with a healthy assist from negative polarization and strong electoral performances, finally established a niche for the trans community within national politics.

It all came to the bafflement of centrists, who, despite all the evidence to the contrary, had decided that it was simply a matter of fact that transgender issues—and trans people—were political liabilities. Rather than account for decades of public policy mismanagement that had left their wing of the party unelectable, they decided that their inability to defeat the right in 2016 was the fault of trans people having the audacity to terrify Middle America with their existence. Leading them would be oligarch and 2020 Presidential candidate Michael Bloomberg, who in March 2019 would refer to transgender women as “some guy wearing a dress,” and that the backlash to their outrageous act of living their lives justifiably explained “where somebody like Trump comes from.” Despite the blatant bigotry and ahistoricity of comments like these, Bloomberg would not face any pushback from liberal pundits. They agreed with him simply because it sounded right.

That this class was (and remains) so quick to throw a marginalized community under the bus before doing even an ounce of due diligence to confirm their bigoted priors speaks for itself. But the more centrists panicked, the more their bellyaching began receiving serious attention—not from the intended audience of Democratic voters, but from Republican elites. Specifically, it would be from the obsessively transphobic faction of the party that, smarting from repeated failures, was looking at any possible excuse to continue with their agenda. Whether intentional or not, centrist Democrats constantly referring to trans rights as electoral poison would end up serving as the fuel that would bring these transphobes back from political death row.

The political context of early 2020 is crucial in understanding how this happened. At the time, Trump was heading into the election year in what seemed to be the strongest political position of his tenure. He had been solidly acquitted by the Senate in his first impeachment trial, made something of a rebound in head-to-head polling against his prospective Democratic opponents, and was enjoying a solid approval rating on the economy (even as voters still disapproved of his administration overall). Seeing this, overeager conservatives started writing post-mortems for the Democrats in anticipation of what they saw as their inevitable victory over the party. And these authors, such as Rod Dreher in The American Conservative, quickly came to a familiar conclusion. Using quotes from hysterical centrist strategists as their source, they proclaimed that Democrats had, once again, ceded Middle America to Republicans. They would, once again, lose to Trump because of it. Specifically, this was because liberals, once again, took positions on issues that authors like Rod Dreher personally disagreed with, among them being support for trans rights.

Following this surge in right-wing self-confidence, transphobia started to make its way back into state-level policymaking. While it would be completely overshadowed in the news by the COVID-19 pandemic, Idaho, on March 30th, 2020, would enact two laws that amounted to the largest attack on trans rights since HB2. One law prevented trans people from changing the sex on their birth certificate to reflect their gender identity. The other made Idaho the first state in the country to ban trans women from competing in female sports leagues. It was a stunningly quick re-entry into the fray, especially remarkable since absolutely nothing had changed on the politics of the issue in just five months.

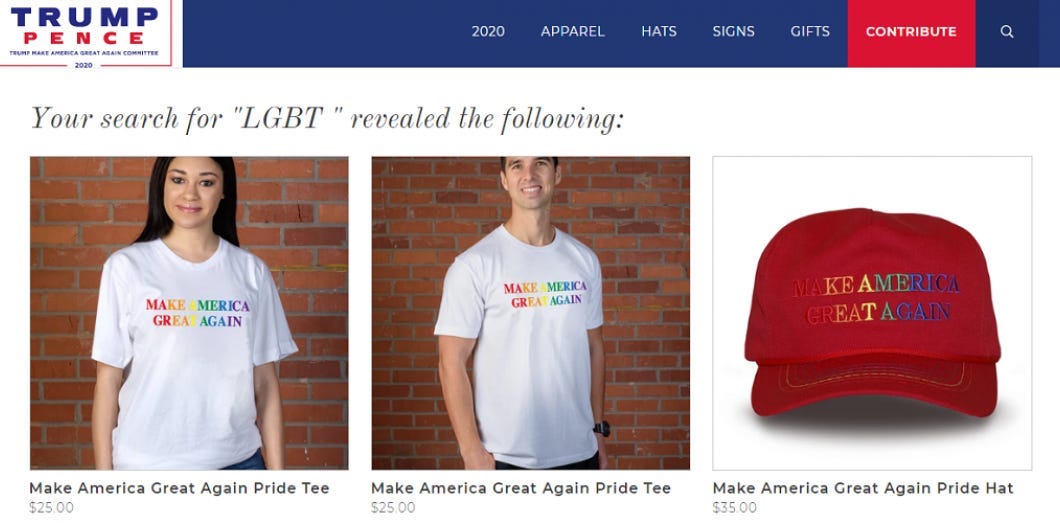

On the part of Donald Trump, the sole leader of the Republican Party in 2020, his campaign and his administration would provide different signals. Rhetorically, the Trump campaign was already pursuing a deliberate effort at moderating their public stance on LGBT issues (it’s largely forgotten now, but improving his numbers among groups that had voted strongly for Hillary Clinton in 2016 was a major part of the President’s strategy in 2020). Richard Grenell, the former Director of National Intelligence and one of the few openly gay members of the Trump administration, was given a speaking slot at the Republican National Convention where he referred to Trump as the “most pro-gay President in history.” The RNC would hire Grenell soon after for a new position focused on LGBT voter outreach. New “PRIDE MAGA hats” were made available on the campaign website. At the end of the campaign, they would even organize “Trump Pride” rallies, where speakers advocated for anti-immigrant policies under the argument that new immigrants threatened gay rights.

These shambolic attempts at pandering would fail to convince even the credulous mainstream media, much less actual LGBT organizations, which are some of the most well-organized interest groups in the country, if not the entire world. Their only response to Republican efforts would be to—correctly—identify them in the context of the administration’s anti-trans policies as attempts to separate the transgender community from their longtime gay and lesbian allies. The Trump administration, which was, at least nominally, separate from the campaign, would go on to respond as if they were trying to prove the accusations right. Over the final months of the campaign, at the same time the Trump campaign was rolling out its supposed “outreach”, the Trump White House would increasingly intensify its attacks on transgender Americans. The Department of Housing and Urban Development and the Department of Health and Human Services announced extensive rollbacks of rules meant to prevent discrimination against trans people from all walks of life, from healthcare to homeless shelters. The Department of Education (unsuccessfully) attempted to ban trans students from participating in school sports nationally, threatening to withhold funds from schools that did not comply.

Still, there were some who thought the administration was not going far enough on the issue. Leading them was Terry Schilling, head of the the American Principles Project of Kentucky gubernatorial infamy. In early August, Schilling sat down for an extensive story/profile with Politico where he detailed his fight to make the conservative movement go all-in on transphobia. He started off by addressing his group’s utter failure in the 2019 Kentucky gubernatorial race, which he said represented a success for his group. The reason was that they found proof that they had swayed “13,000 votes for Bevin.” This may have been minuscule compared to the four-to-seven point rightward swing they promised, but who’s counting? For this reason, Schilling declared, they would take their show on the road for the 2020 presidential race, pushing trans panic for the benefit of Donald J. Trump in swing states across America.

There was just one problem. The Trump campaign, along with what remained of the Republican establishment, were loath to make an issue that they had seen backfire time and time again central to their messaging. Leading this recalcitrance were Jared Kushner and Ivanka Trump, usual bugaboos of the conservative fringe. But one of their allies, curiously enough, would be Pat McCrory himself, who had emerged from his loss in 2016 to serve as something of a ghost-of-Christmas-past, warning Republicans not to rock the boat too hard on culture war messaging. The most notable person in Trump’s circle to support Schilling’s approach was the president’s son, Donald Trump Jr., and it was only because he had gone viral on Twitter talking about the issue in an interview with CBS. But if Schilling was thinking that the son may have been an inroad for influence over the father, he would end up being mistaken. “Trump Jr.,” Politico said, “never gained a nod from his father for the viral moment.”

But regardless of the lack of enthusiasm from the President for his project, Schilling was committed to pushing forward anyway. He admitted that the stakes were existential, for both his organization and his movement: if they “raised all this money” and “still [came] up short”, their support would dry up and the APP would cease to function. Just like in Kentucky, they would go all in, leaving nothing on the field in terms of effort or rhetoric. By the end of the cycle, the APP was reportedly sending “tens of thousands of anti-trans texts every hour” in key swing states, accusing Biden of endorsing sex changes on 8-year-olds. Schilling was so confident that this tawdry smear would be effective that he went around to local media outlets gleefully admitting that it was a lie—implying that there was nothing anyone could do about his devious schemes even if he teed it up for them.

But, as in Kentucky, it would be the voters who would test his hubris.

Once again, it was a flop.

Despite the endless confidence of the right in their supposed connection to the average American, Trump would be defeated decisively at the national level, losing by over 7 million votes, or 4.5 percent. Things were closer in the swing states, but Biden would win nearly all of them still. After all was said and done, it was a fairly decisive victory by the standards of modern Presidential elections, and only the fourth defeat of a sitting President since Herbert Hoover. If Shilling and his ilk were to be judged by the usual standards of failed Presidential campaigns—as they expected to be—they would have had many cold days and weeks ahead of them. Just like in North Carolina, just like in Alabama, and just like in Kentucky, transphobes went all-in and ended up with nothing.

But it would soon be clear that the results of the 2020 election would be judged far differently than the usual standards. Republicans were not only unwilling to admit that their policies, tactics and politicians were unsuccessful in winning them the election—they weren’t willing to admit that they even lost the election in the first place. This was most obvious in the actions of Donald Trump himself, but it was more than just him. Across the right, there was simply an inability to reckon with the death of the Myth of 2016, where, when all was said and done, Middle America was always on their side. When this collective nervous breakdown culminated in the debacle of January 6, the right found itself entering four years of a new Democratic administration in the wilderness. Their leader had gone insane, they had no broad message, and said insane leader was preventing them from even attempting to find a new one.

But at the same time, there were no efforts by Democrats to use their new popular mandate to push Republicans around—because they didn’t believe they had one in the first place. Biden’s victory was decisive in a vacuum—his winning margin was second only to Obama’s 2008 victory in size in the 21st century—but compared to pre-election expectations of a sweeping landslide, it might as well have been a loss in the eyes of many. In the months after November, and even after the party secured a trifecta in January, a new cottage industry of pessimistic doomsaying sprouted up on the right of the Democratic Party.

Their argument was simple: 2020 was the best position the party could have ever asked to be in, with a popular candidate and an unpopular incumbent. But because liberal elites pushed their cultural preferences too far, a chance for a real Democratic majority was fumbled. Now the party, facing a Senate and electoral college map with structural biases against them, was on a course to be out of power for a generation. Some were even so hysterical that they proclaimed that the modal outcome by 2025 was Donald Trump coming back to power with a filibuster-proof majority.

Their solution: the party should move to the right.

How novel.

The purpose of this push, of course, was to shout down and shut out the left. But its most receptive audience would end up being the transphobic far-right. This wasn’t necessarily because these figures specifically singled out support for trans rights as a weakness for Democrats—in fact, some even (correctly) identified it as a popular position. But their broad narrative—that Democrats were out of touch, Republicans were set to “dominate America’s federal institutions,” and that it was all the fault of elite liberal activists—was music to the ears of the anti-trans fringe. It was exactly what they themselves had been saying—and unsuccessfully attempting to put into practice—for years.

Pushing this exact case most vociferously was none other than the APP, who would lay out its plan for the future of the Republican Party in a mid-2021 report entitled “MAGA after 2020: How the GOP Can Win Again and Save America.” The vision laid out in this piece is immediately recognizable to anyone today who has seen a single clip of Tucker Carlson, a tweet from Matt Walsh, or a speech by a Republican politician over the past two years. It presented a conception of American party politics as a world where Republicans stood as the party of the working class, who were united by, if not outright cultural conservatism, then a shared set of “anti-woke” attitudes. Democrats, on the other hand, were an elitist, radical minority, only able to impose their will over the populace through their control over cultural, technological, educational, and (in a nod to election deniers) electoral institutions.

To prove this, they extensively quoted the likes of James Carville, Abigail Spanberger, and David Shor. Shor, in fact, was someone they were particularly fond of. Proclamations from him like “most voters are not liberals…If we polarize the electorate on ideology…we’re going to lose a lot of votes” and “the GOP has very rosy long-term prospects for dominating America’s federal institutions” fit exactly within the APP narrative. All told, quotes from the strategist would make up a full page’s worth of text in the document alone.

In bringing this up, I’m not trying to say that center-right Democratic figures like him were the sole reason, or even a main reason, as to why the Republican Party re-configured itself in the way it did in early 2021. Transphobic groups are the ones who did that. But by being so irresponsible in their predictions and prescriptions, these figures ended up fueling transphobic groups. Their carelessness would provide a supposedly empirical basis for those who wanted to make staunch opposition to “wokeism” central to the post-Trump Republican brand.

After all, who in the GOP could argue against the likes of Terry Schilling when the enemy themselves were admitting that he was right? Applying this perspective to their own priors, their fundamental thesis would be, in their own words:

“Trump actually broadened the Republican base by tying Democrats to their most unpopular positions: wokeism, and its related issues. And should Republicans continue to successfully deploy this strategy, there would appear to be ample room to expand the party’s coalition even further in the elections to come.”

Whether or not it came directly from the APP or their allies, this theory, more or less, has come to dominate the GOP’s understanding of politics throughout Biden’s tenure. For as ineffective as groups like the APP had been at actually persuading voters, they would prove masterful at synthesizing the various anxieties, power vacuums, and bigoted inclinations that made up the post-Trump GOP into a unified theory of politics. At the same time, it was something that the entire party could get behind and served to push the exact issue the fringe had been obsessed with for years.

Thus came the deluge.

As the Republican Party started to conceptualize its very identity around strident “anti-wokeism”, a massive wave of anti-trans policymaking began to rise, starting in the country’s reddest states. In just the first four months of 2021, over 250 anti-LGBT bills were proposed, and 17 were passed: more than any year since 2015. Following the playbook pioneered by the APP, many of these bills specifically targeted children, with seven states passing sports bans and one, Arkansas, outright banning gender-affirming care for trans kids. Post-HB2 apathy had been replaced almost overnight with a sudden fervor.

This fervor would also show up on the campaign trail. New Jersey and Virginia would both be holding their regularly scheduled off-year gubernatorial elections in November, with Governor Phil Murphy running for re-election in the former and an open seat in the latter. Republicans in both races ran campaigns straight out of the APP playbook, pushing against protections for trans children in public schools, along with the teaching of the racial history of America (termed “Critical Race Theory”), all under the guise of “parental rights.” For two states that had both voted for Biden by over double digits in 2020, it was quite a bold gambit, given that conventional political wisdom since the beginning of time has always held that cultural issues are always the thing you are supposed to moderate on first in unfavorable states.

This time around, however, the strategy would not be an abject disaster. Benefitting from political tailwinds, Republican candidates in both states, Jack Ciattraelli in New Jersey and Glenn Youngkin in Virginia, solidly outperformed Trump’s 2020 numbers. The latter won his race outright. Those both on the right and the left interpreted it the same way: as proof that the right had, through “anti-wokism”, found a terrifyingly effective new political weapon that they could use to rout Democrats up and down the ballot in 2022.

Even at the time, it would have been reasonable to wonder if this was something of an overreaction. Not only did those hyping up the importance of “anti-woke” messaging in the race ignore the many, many instances of the exact same strategy failing in the past, but it also failed to account for the extent to which the results may have simply been a function of the national environment. Both races occurred less than two months after the fall of Kabul and the subsequent collapse of Biden’s approval ratings. Given how salient the question of Biden’s performance was at the time, it would have been worth considering if the results in both states were more of a function of thermostatic partisanship than the efficacy of any new strategy on the part of Republicans.

Curiously enough, in fact, the margins in both races almost perfectly match what you get if you add Biden’s net approval on Election Day, 2021, with each state’s partisan lean. For all of the credulous profiles of Chris Rufo that followed the races, very little had actually been proven to say that anti-trans rhetoric was actually effective.

It would still be more than enough, however, for Republicans to embrace it and other assorted causes as the heart and soul of their national strategy in the 2022 midterms. Nearly every single Republican candidate in every major race in the country that year would engage in transphobic or “anti-woke” rhetoric to some extent. To cover the story of every single one of these campaigns would be well beyond the scope of a single article. Instead, I will do the best I can to summarize by making a list of Republican candidates in crucial races in the 2022 elections, the kind of rhetoric they engaged in, and what the ultimate result was, to see if this rhetoric had finally become effective.

Michigan, Governor: Tudor Dixon (R), challenging Gov. Gretchen Whitmer (D)

Quote: “Gretchen Whitmer has embraced the trans-supremacist ideology, which dictates that individuals who are born as men can be allowed to compete against our daughters.” - Tudor Dixon

Result: Defeated in the general election by 10.5% in a R+2 state in a R+1.6 year (Raw underperformance: 14.1 points)

Wisconsin, Governor: Tim Michels (R), challenging Gov. Tony Evers (D)

Quote: “Tony Evers has betrayed parents time and again, but this is the last straw. He's proven once and for all that he will always choose fringe social agendas.” - Tim Michels

Result: Defeated in general election by 3.4% in a R+4 state in a R+1.6 year (Raw underperformance: 9 points)

Pennsylvania, Governor: State Sen. Doug Mastriano (R), challenging Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro (D)

Quote: “I've already introduced legislation to prohibit gender reassignment surgery…As governor, on day one, I'll be signing an executive order and then codifying that into law in the General Assembly.” - Doug Mastriano

Result: Defeated in general election 14.7% in a R+4 state in a R+1.6 year (Raw underperformance: 20.3 points)

Pennsylvania, Senate: Mehmet Oz (R), challenging Lieutenant Governor John Fetterman (D)

Quote: “85% of young children who say they're transgender will go back to their biologic (sic) sex.” - Mehmet Oz

Result: Defeated in general election by 5.0% in a R+4 state in a R+1.6 year (Raw underperformance: 10.6 points)

Nevada, Senator: Former Nevada Attorney General Adam Laxalt (R), challenging Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto

Quote: “They're just, you know, your classic coastal radical leftists. And so, you know, kudos to DeSantis for signing this [Don’t Say Gay] bill. And then for going on offense.” - Adam Laxalt

Result: Defeated in general election by 0.8% in a R+2 state in a R+1.6 year (Raw underperformance: 4.4 points)

Arizona, Governor: Kari Lake (R), challenging Arizona Secretary of State Katie Hobbs (D)

Quote: “Gender is determined by God at conception.” - Kari Lake

Result: Defeated in general election by 0.6% in a R+4 state in a R+1.6 year (Raw underperformance: 6.2 points)

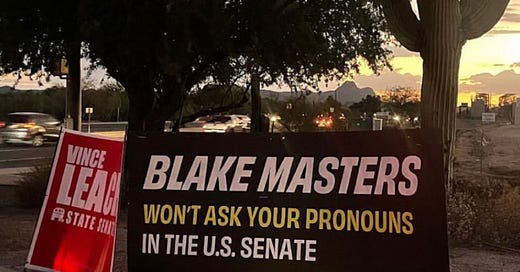

Arizona, Senator: Blake Masters (R), challenging Sen. Mark Kelly (D)

Quote: “When I’m in the U.S. Senate, I will push a federal version of the Florida [Don’t Say Gay] law.” - Blake Masters

Result: Defeated in general election by 4.9% in a R+4 state in a R+1.6 year (Raw underperformance: 10.5 points)

Minnesota, Governor: Scott Jensen (R), challenging Gov. Tim Walz

Quote: “Why are we telling elementary kids that they get to choose their gender this week? Why do we have litter boxes in some of the school districts so kids can pee in them because they identify as a furry? We’ve lost our minds.” - Scott Jensen

Result: Defeated in general election by 7.7% in a D+3 state in a R+1.6 year (Raw underperformance: 6.3 points)

New Hampshire, Senate: Gen. Don Bolduc (R), challenging Sen. Maggie Hassan (D)

Quote: “Identifying as a cat, hissing at other students, meowing during tests, licking themselves like cats do to clean themselves. Very, very disruptive behavior, very unnecessary behavior, and behavior that doesn't belong in the classroom. And nobody can do anything about it.” - Don Bolduc

Result: Defeated in general election by 8.9% in a D+3 state in a R+1.6 year (Raw underperformance: 7.5 points)

Georgia, Senate: Herschel Walker (R), challenging Sen. Raphael Warnock (D)

Quote: "I don't even know what a pronoun is." - Herschel Walker

Result: Defeated in runoff election by 2.8%, in a R+4, state in a R+1.6 year (Raw underperformance: 8.4 points)

Every single one of these contests were races which Republicans, all else being equal, should have won, or at least come close.

Transphobia was, and is, the dog that couldn’t hunt.

As an aside, it would be a good thing if every single pundit or political figure who has ever referred to trans people as political liabilities—from Hillary Clinton to Bill Maher—was to asked a simple, binary question: are they too stupid to do basic due diligence on the issues they feel compelled to speak about, or are they concern-trolling bigots? It’s either one or the other. They are either incapable of doing the basic research that shows that Republicans are not succeeding on these attacks, which means these figures should never be seen as credible again. The alternative is that they know that Republicans are failing, and are simply lying about it to scare people and further a reactionary, transphobic agenda. I am curious as to which of these two things turns out to be the case.

Going Forward

Despite their debacle of a campaign strategy failing to a truly unbelievable degree in the midterms, Republicans have only intensified their rhetoric and actions on the issue in the months since. Red states have introduced a flood of anti-trans bills during the current 2023 legislative sessions, with their targets already moving from children to all transgender adults. Some have already passed. Many more will soon be in states where Republicans have full control. For Terry Schilling, this is simply everything going along as planned. His organization's long-term goal, as he told the New York Times, is to “eliminate transition care entirely.”

It’s hard not to feel somewhat shocked or intimidated by the speed at which Republicans have picked up this issue and how extreme they have become in such a short time. Some are even attempting to bring back bathroom bills! Much of the current discourse around this push has rested on the implication that this in and of itself represents something dire about the state of public opinion. We’re inclined to view the Republican Party as a sort of hyper-competent, Machiavellian super-organization: the same institution that pulled off the Reagan Revolution, stole the 2000 election, and took over the American court system. It’s easy to feel like that if such a party is moving so hard and so fast against trans people, it must be because they know it’s a winning issue. It must be because they discovered some latent strain of bigotry in the public that they are now exploiting, dispassionately, for political gain.

If there’s one thing I hope to get across from this article, it’s that the anti-trans movement should not be afforded anywhere near this level of deference. This is not a project that has come from the public. It has arisen, in every sense, from the elite level of conservative politics. It also has an extensive electoral track record, and it is an incredibly poor one. From North Carolina in 2016, to Kentucky in 2019, to the midterm elections in 2022, attempts by Republicans to change the course of any race leveraging anti-trans fear have been met with failure. At best, their efforts have just been unable to break through, even with very right-wing voters in very red states. At worst, it has outright cost them votes.

But if transphobia has been such a consistent failure, why do Republicans keep pursuing it? The answer has more to do with emotions than strategy. Much like the old demographics-as-destiny theory that captured the Democratic Party in the 2000s and 2010s, anti-trans, or, more broadly, “anti-woke” lore is the right kind of story for the right political class at just the right time. Rather than making anxious and leaderless Republicans tackle the hard questions as to why they keep losing, it tells them that victory is right around the corner, that their enemies are utterly monstrous, that “the people'' already agree with them, and that the only changes that need to be made involve doing even more of what they already want to do.

It also should not be forgotten that these people actually believe in what they are pushing. Elite conservatives, especially those who rose to prominence during the Trump era, are true believers in every sense of the term. They were educated in cloistered, conservative schools, work exclusively with people who think like them, and have few interactions with people outside of their circle that are not confrontational in nature. It is the only sort of upbringing that any politically educated person who actively works for Donald Trump could have. They live and breathe an ideology that worships traditional hierarchies and sees any deviation from the norm as an existential threat.

And to them, nothing represents such a deviation more than trans people. This is why they specifically have been chosen as their post-Obergefell targets. And as they spend more and more time in their own echo chambers, becoming more and more convinced that the world is falling apart around them, attacks on trans people become increasingly less of a means to an end and more an end in and of themselves. They see what they do as a moral good—a last stand to save society itself from destruction. In this context, persisting with their obsessions, even after repeated electoral failures, is nothing less than virtuous.

That’s the upshot to all this. Transphobes aren’t pushing transphobia because trans people are easy targets for political gain. They do it because it makes them feel better about their own failures, and because they are ideologically obsessed, out-of-touch psychos with apocalyptic delusions.

But if trans people aren’t political liabilities, what are they? What role does the question of trans people play in electoral politics? The answer is both simple and somewhat maddening: it is a low salience issue. Trans rights, gender ideology, bathroom bills, girls’ sports—all of these are debates that the vast majority of the American public, including most conservatives, does not care nearly enough about to decide their vote. It is largely seen as an intimate, personal question—not something where politicians need to be involved.

This can work both positively as well as negatively. While general public apathy towards the issue means that voters are exceedingly unlikely to vote for Republicans because of anti-trans messaging, as has been extensively demonstrated, it also means that politicians who pass anti-trans laws are not likely to face significant electoral pushback over it. This is why Ron DeSantis (who was already a popular governor before he became a nationally-known culture warrior) was able to win by as much as he did in 2022. From this, you can project that, in the absence of federal legislation, our current trajectory is for the state of trans rights in the United States to be polarized starkly along state lines. In blue states, where voters have been negatively polarized by Republicans into support of trans rights, there is the chance for the passage of world-class protections for trans people, such as the shield and sanctuary laws recently enacted in Minnesota. In red states, we will reach a situation where transitioning and nontraditional gender identities are essentially criminalized, as is currently happening in Tennessee.

At the federal level, the fate of trans issues will be like the fate of all other low-salience issues: bound to the broad tides of history. Perhaps Joe Biden could make another career comeback, reach positive approval, smash whatever Republican candidate he faces in 2024, and come into a second term with a trifecta. In that case, we could end up with nationwide trans protections, which the President has backed for a surprisingly long time. It’s also possible that he or Kamala Harris could be defeated by a Republican because of a poor economy, and that this Republican could use their own trifecta to assault trans rights around the country. It is simply impossible to predict right now. The one thing we can say with certainty is that the more Republicans focus on this issue, the less they’re focusing on the problems voters actually care about. Every time they give a speech or pay for an ad about top surgery, they drive themselves that much out of alignment with the voters and that much further from power.

So, if you want a vision of the near future, it may not be the public triumphantly rising up in support of trans rights, or the masses being spellbound by the likes of DeSantis into a frothing hatred. The most likely image will be that of Roy Cooper on Election Night, 2016, successfully using the issue to win a race he should have lost, coming onto stage for his victory speech, forever. This may be little comfort for trans people across the nation, especially those living in red states.

But for the conservative intelligentsia, it should terrify them.

Good stuff, big shout out to David Shor and his fellow pundits convincing the GOP their missing votes could be found at the bottom of a canyon, wouldn't have happened without them.

On Maher and Hillary, I think both scenarios apply: they're boomers whose reference for trans people is, well, men so gay that they want to remove their dicks. Extra gay. But they're also very afraid and convinced that every joke Reagan made about the libs is true, so the words "you're out of touch" trigger a Pavlovian response to them. It doesn't excuse them being bigots or being unable to read, but it does explain it.

the republican party are nothing but monsters. anyone who votes for their bigoted party are themselves monsters.